By Laura Dougherty, associate principal, Cushing Terrell

In Colorado’s mountain towns, where developable land is scarce and demand for both workforce housing and visitor parking keeps growing, one unlikely solution is emerging: the parking garage.

While the market has cooled slightly, home prices particularly in mountain communities through Colorado are still rising faster than the state average and prices haven’t come down substantively from the COVID buying boom. Across the Mountain West, home prices in many resort towns have surged more than 70% in just three years. At the same time, long-term rentals are disappearing as second homes increase—tightening an already constrained housing market.

In places like Telluride and Estes Park, that pressure is prompting a new mindset. These communities know they need workforce housing. They need services for a growing community. They need parking outside of the core of town to avoid congestion and preserve the community’s character. So together, our team at Cushing Terrell has been helping these communities envision scenarios where public parking is no longer a single-use utility but as a foundation for mixed-use design, bringing housing, childcare, and mobility infrastructure together in one place.

These “two-for-one” developments can help towns make the most of limited space while softening the footprint of large infrastructure on sensitive mountain landscapes. It’s a practical, people-first shift: designing one project to solve several community needs.

The Two-for-One Opportunity

Every mountain community faces the same dilemma: too little land, high construction and land costs, and environmental limits that make sprawl impossible. In a place like Telluride, where every acre must pull double or triple duty, a surface parking lot can be transformed into a mixed-use hub that supports local workers, visitors and families at once.

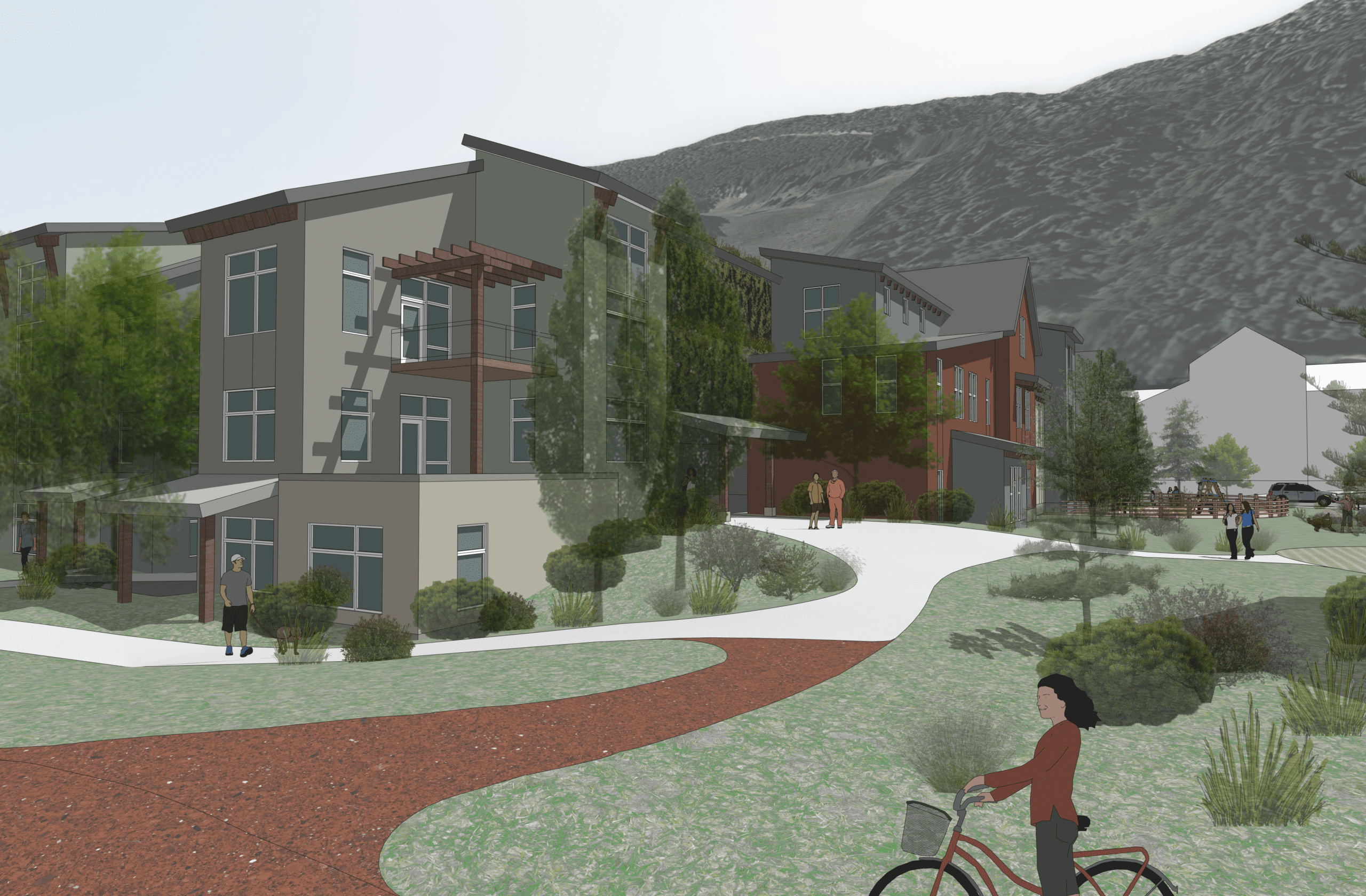

At the Lift 7 Neighborhood and Lot L project, Cushing Terrell and project partners are working with the Town of Telluride and Telluride Ski & Golf Company on a plan to turn an existing surface parking area into a 900-space intercept garage with about 50 affordable homes, a childcare center, and neighborhood-serving retail and transit amenities. The plan consolidates parking from nearby sites, freeing other parcels for open space and workforce housing, while creating a centralized hub where people can park once and move about town by foot, bike, or shuttle.

The urgency is clear: like many resort communities, Telluride faces a seasonal surge in workforce demand that outpaces available housing. The Lift 7 project helps address that imbalance by combining new workforce homes with needed infrastructure in one coordinated plan.

When space is tight, stacking uses—vertically, efficiently, and with care—becomes a form of sustainability. For tourism-driven towns struggling to house the workers who keep them running, this kind of land-use efficiency marks a major shift: treating infrastructure as shared civic space, not a single-use burden.

Designing for Scale and Character

When mountain towns hear “parking structure,” the reaction is often cautious. A 900-car garage in a historic setting could easily overwhelm its surroundings if not handled carefully.

That’s why the Lift 7 and Lot L concept takes a layered approach. Parking is mostly buried below grade or wrapped with housing on three sides, screened with locally contextual materials, and framed by pedestrian-scale streetscapes. Residential units step down toward the San Miguel River, with massing broken into smaller forms that echo Telluride’s rhythm of pitched roofs, timber detailing and human-scaled facades.

On the ground level, amenities like childcare, bike storage, and small retail add everyday life and activity. Above, affordable apartments will house people who already live and work in Telluride—what locals are calling “smart housing and efficient parking.”

The mix of studios, one-, two-, and three-bedroom units serves a range of income levels, from seasonal employees to year-round residents—critical when you consider the median listing price for a home was about $3.6 million as of August 2025. The 4,000-square-foot childcare center and compact retail spaces reflect community priorities identified through multiple rounds of public engagement.

By maintaining view corridors, protecting riverfront vegetation, and adding a park that connects to the San Miguel River Trail, the project balances housing, parking, and public space within a mountain context that can’t absorb excess. This isn’t density for density’s sake, rather it’s design with purpose that serves the people who live here.

These moves transform what could have been a monolithic structure into something that feels rooted in place. That’s the difference between a project that simply fits and one that truly belongs and is a good neighbor.

A More Connected, Less Car-Dependent Future

Projects like Lot L also advance a broader transportation strategy. Telluride’s master plan calls for an “intercept” model, where visitors park on the edge of town and travel the last mile on foot, bike, or shuttle. It’s a concept that echoes European mountain towns like Chamonix, where vehicles are kept outside the core and pedestrian life takes center stage.

In Telluride, Lot L anchors that idea with a transit-oriented hub and a reimagined streetscape along Black Bear Road that prioritizes people over vehicles. The garage becomes a true connection point, consolidating commuter parking, shuttles and resident access in one efficient system.

As the town invests in bridge upgrades, trail extensions and safety improvements along Mahoney Drive, each project moves toward the same goal of expanding transportation options while easing congestion. From our perspective, the future of mobility in mountain towns shouldn’t be defined by how many cars we can park, but by how easily people can move without them.

Lessons for Other Resort Communities

Telluride’s Lift 7 project is still in design, but it’s already shaping how we think about land use in other mountain towns.

In Estes Park, where Cushing Terrell is helping evaluate options for structured parking paired with workforce housing, the same questions are guiding design: How can parking investments also serve housing goals? And how can infrastructure strengthen, rather than strain, small-town character?

Across our work in mountain and resort communities, several lessons continue to emerge for communities seeking to maximize impact and minimize footprint:

- Co-locate with purpose. Combine parking, housing, and community uses to maximize land efficiency.

- Design for scale. Break down large structures into smaller forms with residential edges and local materials that fit their setting.

- Think multimodal. Make parking a gateway, not a destination. Connect it seamlessly to shuttles, trails and public spaces.

- Preserve character. Let new structures inherit the language of place: steep roofs, natural materials, and walkable edges.

- Engage early and often. Public participation ensures infrastructure investments reflect real community priorities.

Mountain towns can’t afford single-use solutions anymore. When parking and housing evolve separately, traffic, cost, and scarcity follow, eroding the very sense of place that drew people there in the first place. The next generation of projects aims to reverse that trend, turning what was once pure infrastructure into livable, layered community fabric.