By Susan Pratt Reinhardt, AIA, associate principal, Lean Project Consulting, Inc.

A construction project is an organization composed of approximately 600 individual companies (including suppliers) with separate contracts, fees and scopes of work, invented to build a single, very expensive product that is then instantly disbanded. It should be no surprise that coordination issues, including paperwork, consume 70 percent of work time onsite — the average craftsperson spends only 30 percent of their day doing actual work in the field.

Large construction projects are typically up to 80 percent over budget and take 20 percent longer than scheduled (McKinsey, 2016). The U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that productivity in our industry has steadily declined since 1964. Owners complain of a lack of innovative ideas, unclear design documents and expensive change orders. Architects complain of low fees and short timelines. We hear that technology will save us but think of all the technological advances since 1964: cordless hand tools, BIM software, laser levels, GPS, the Internet, tablets — even plywood. Yet productivity hasn’t budged!

There is a way out however, through fostering team collaboration. Lean (the Toyota Production System) in the building industry, is a relatively new philosophy for achieving innovative projects on schedule and under budget. Lean was adapted to construction 20 years ago by Glenn Ballard and Greg Howell, who realized that steam-lining the operations of one trade had no effect on overall project schedules. After surveying several projects, they realized that workers typically completed only 54 percent of the work planned in any given week. When one trade doesn’t complete a task, it reverberates through every downstream trade: The Last Planner® System was born.

There is a way out however, through fostering team collaboration. Lean (the Toyota Production System) in the building industry, is a relatively new philosophy for achieving innovative projects on schedule and under budget. Lean was adapted to construction 20 years ago by Glenn Ballard and Greg Howell, who realized that steam-lining the operations of one trade had no effect on overall project schedules. After surveying several projects, they realized that workers typically completed only 54 percent of the work planned in any given week. When one trade doesn’t complete a task, it reverberates through every downstream trade: The Last Planner® System was born.

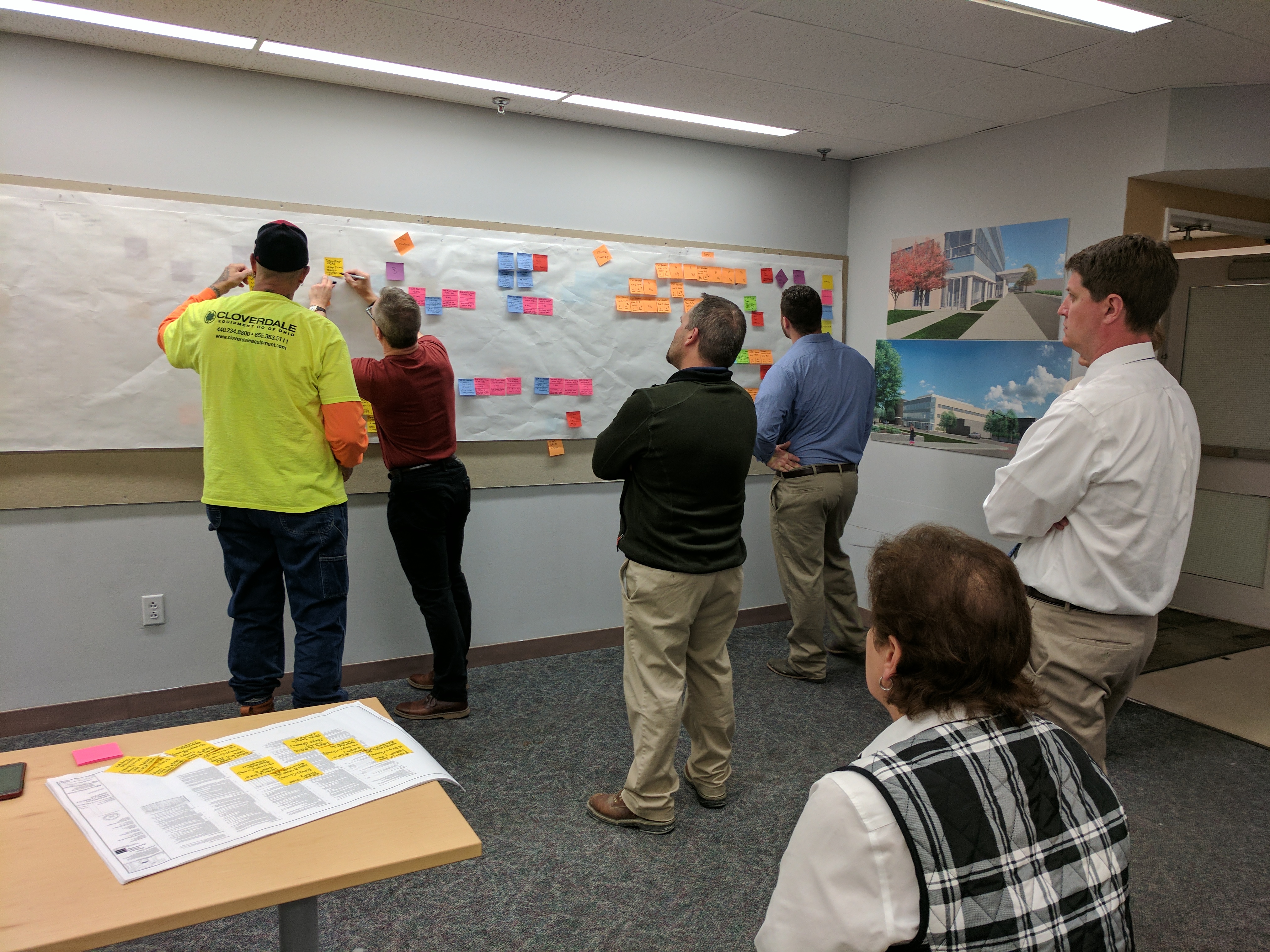

With the Last Planner® System, the general contractor shares what milestones must be reached to keep on schedule. Trade foremen (the “Last Planners”) negotiate with other trades and the GC about how they will reach that milestone. Each week, the foremen look six weeks ahead for roadblocks that must be removed before new tasks can start – missing information, materials, equipment, etc. As tasks move into next week’s work plan, they are free of constraints: trades in each area can coordinate their work and perform tasks as expected, and keep to the overall schedule. Adversarial relationships fade, and trust is established.

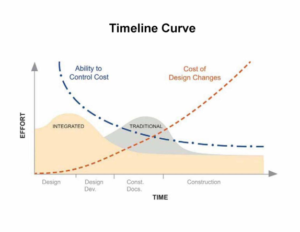

Lean is also vital in the design phase. Typically, architects rush to get owner approval of a floor plan and ask users to sign off on drawings and recommendations they may not understand, so they can get their engineers moving. According to Neenan Archistruction, within the first 15 percent of design, 80 percent of costs are set: massing, exterior skin, structure, fenestration, and overall mechanical/electrical systems are already determined, with major impacts on the budget and schedule. The possibility for real innovation thereafter is greatly reduced.

True collaboration, with major trades and engineers involved from the beginning, creates savings that no team working in silos would even notice. If highly reflective paint is specified in the classroom, we can decrease lighting levels by 25 percent or more. This decreases the heat load, which has a significant impact on the mechanical system. Expensive, super-efficient windows and upgraded insulation may allow us to eliminate the perimeter heating system with all of its ductwork. Teams working together could save thousands on the mechanical system — perhaps buying an off-the-shelf rooftop unit instead of a custom unit. Yet these discussions often don’t occur. Instead, the architect leaves room for the air handling units, then the mechanical engineer waits for all designing to stop before inserting whatever system he used in previous projects, using rules of thumb for that project type. The electrical engineer has his own rules of thumb, independent of the specific design. The interior designer chooses colors based on aesthetics and never meets the engineers. Architects make the ducts fit the structure. But what if project-level conversations happened up front with builders of major systems in the room?

A hospital group in Ohio inherited a project for a 62,000-square-foot medical office building with emergency department, imaging, and family medicine practice. Estimated at $37.7 million, they had a budget of $32 million. The hospital decided to use lean methods for the first time. Major contractors were hired up front, and designers, owner groups, and tradesmen divided into cross-functional groups to study mechanical systems, interiors, skin, and other components. Every week, these groups discussed options and how to integrate systems. A representative from each discipline formed a Core Team empowered by their organizations to make final decisions.

Over time, departments had adopted a belt-and-suspenders approach; the clinic challenged departments to review these standards — what was actually needed by the patient? The team challenged sole-sourced materials, standardized custom curtain walls, redesigned curtain wall attachments, changed the steel design and how concrete was poured. After consultation with the city, the garage was replaced by onsite parking, losing only a few spaces. The team decreased the budget without removing scope, and brought the project in at $30.7 million.

The owner said of her Core Team: “I spent so much time with them, they started thinking like me — they made wholistic decisions and consulted each other, whether I was there or not, and that was very reassuring. I knew they would look at the problem from all appropriate angles and decide. We did not wait for an executive to make decisions — and sorry, he is gone for two weeks so everything stops. We answered questions quickly, kept the project moving, and paid everyone on time — the things that matter.”

For innovation, create teams that engage the owner as a partner in design. Build trust, rediscover joy in building, and enjoy the results.

Images courtesy of LeanProject