What comes first, a healthy building or an energy efficient one? A worldwide pandemic is shining a spotlight on the need for buildings that protect occupant health. Unfortunately, this exercise is likely to identify that for too long, our industry has been much better at making the business case for energy efficiency than health. But what if we reverse this approach and quantify health impacts before pitching energy benefits?

The need for revising our approach is easily explained in this everyday example. How many times have you faced the following scenario on a project? You or your team identifies a solution that may result in lower energy use, called an “Energy Conservation Measure” (ECM). An energy modeler then calculates the potential energy savings. The simplest form of assessing the ECM’s merit is to divide the first cost by the expected savings, which yields a simple payback period.

Now consider the next step if that answer is five years. What if it’s 10 years? Or how about 20? This is often where energy efficient solutions are cut from projects. If somebody is an advocate for the solution, perhaps they bring out other associated benefits to try and justify it. These sometimes relate to indoor environmental quality (IEQ) or health, but they are almost exclusively qualitative arguments. For example, “better air quality” could be mentioned as a benefit, but without metrics, it’s a qualitative statement.

Unfortunately, this example plays out every day. As a result, projects miss opportunities to incorporate solutions that not only save energy, but also protect occupant health and increase productivity.

In order to change this narrative, we need to understand the intrinsic value of health, as well as how it relates to energy.

Certification programs like the WELL Building Standard have drawn attention to existing research on facility costs. In simple terms, the 1-10-100 rule states that for every one dollar spent on energy, an organization spends 10 dollars on rent and operations, and 100 on employee salaries and benefits. Despite this relationship, most building analysis focuses on quantifying the lowest value – Energy.

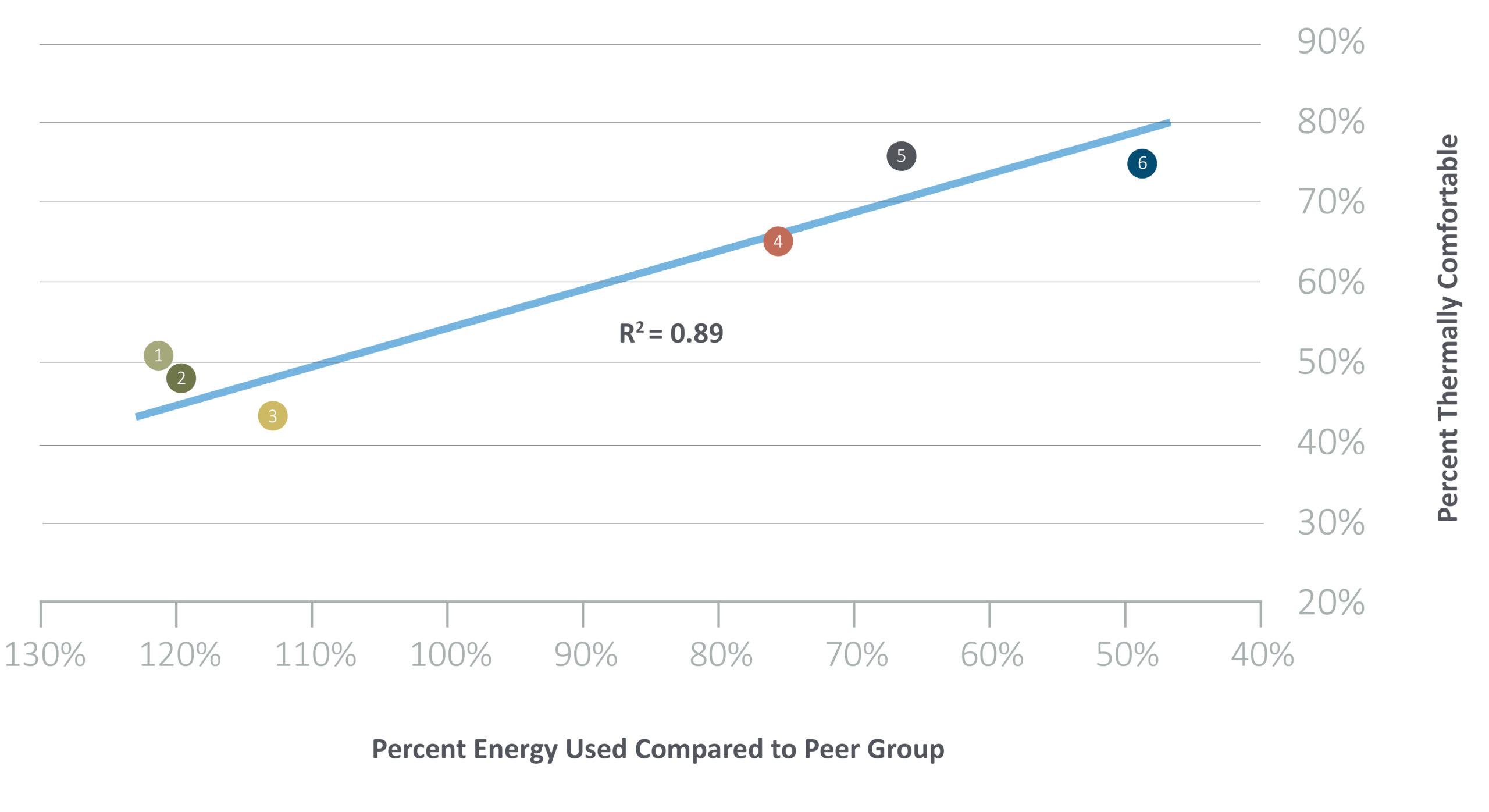

Meanwhile, our own research at BranchPattern shows a strong relationship between energy and health. In one such example (see Figure), we surveyed over 2,000 occupants in six new and recently renovated buildings constructed over a decade, including multiple LEED certified projects. All of these buildings were designed and intended to be energy efficient. But we can clearly see a relationship between the thermal comfort scores and actual energy use in the building.

Diving deeper, we found that energy use increased wherever the facilities teams were required to solve thermal comfort complaints. This led to increased energy use above what had originally been modeled. We see this relationship between energy and occupant comfort play out time and time again.

Understanding this relationship has changed how we work. While energy and carbon reduction are still important to us, we’ve realized that if we want to successfully make the case for low-energy systems, we need to also appeal to the decision-makers that focus more on people than projects.

One way BranchPattern has addressed this is by developing our own tool called happē (health and productivity performance estimator). It leverages peer-reviewed research and data to better quantify the associated health and productivity benefits of design strategies into the modeling process. It also allows us to accomplish our goal of designing healthy buildings that have better actual energy performance in operations.

We recently applied this tool on a 180,000-square-foot global headquarters for a data analytics company. The design team had proposed using an underfloor air distribution (UFAD) mechanical system as a way to save energy, but also because UFAD systems are shown to have better temperature control and indoor air quality. In this case, the system required an additional $2.6 million investment over the standard system. Through energy modeling we determined that the energy savings yielded a 21-year payback. In most cases, that result would usually remove the concept from consideration.

However, by using happē, we were able to present the health benefits in metrics tailored to their organization. These included $4M per year in productivity improvements, and a 17 percent reduction in rates of influenza. These benefits dwarfed the energy savings in value to the organization, who ultimately led them to install the system.

Designers need to better understand that health and energy are related, but health is a far more powerful driver in decision making. This requires that we move past presenting health benefits as secondary to energy savings during the design process. In order to do that, we must have discussions about health benefits early, and present the results in terms that an organization values. By doing so, designers will find they’ve unlocked a new path to even more energy efficient buildings.

Pete Jefferson, PE, WELL Faculty, LEED-AP, HBDP is a Principal at BranchPattern, a building consultancy with offices nationwide. He consults with project teams to help them achieve building performance outcomes that are human-centered, environmentally-responsible, and mission-driven. Through BranchPattern’s Building Science team, his work bridges research with practice.